Subsidence might be your first fear when cracks mysteriously appear from nowhere. And while you will know that living with wonky walls and the occasional sticking door is part of the ‘old house experience’, unexplained or sudden structural movement gives you right to be concerned.

Most old buildings show signs of past movement, such as wavy brickwork, doors trimmed to fit distorted openings, or sloping floors with strips of beading concealing gaps at skirting boards. But, in most cases, the movement will have stabilised and there is no cause for alarm.

Knowing when to be concerned is essential if you are renovating a property. We look at when a crack is a sign that you should investigate further and what can be done to rectify the problem.

This feature is an edited extract from the Victorian & Edwardian House Manual by Ian Rock, published by Haynes. Ian Rock is a chartered surveyor and director of survey price comparison website rightsurvey.co.uk

Wonky door frames add to an old house’s charm but can be a sign of active structural movement

What is subsidence?

The word ‘subsidence’ refers to the ground beneath foundations giving way, robbing the wall of support and causing it to drop, cracking in a typical ‘V’-shaped pattern. This puts strain on the home, destabilising the walls.

So why does ground collapse happen?

What causes subsidence?

- The effects of droughts, tree roots and heavy frosts can cause clay subsoils to violently shrink or swell.

- Leaking drains can turn the ground under your house into soft, squelchy marshland.

- Nearby excavation work, such as an extension being built next door, can also be a destabilising influence.

- Sinkholes and old mine workings can cause subsidence, but this is extremely rare.

There is, however, another type of downward movement that commonly gets mistaken for subsidence – settlement. This is not usually a serious concern because most buildings gradually settle over time as the ground is slowly compressed as it adjusts to new weights imposed upon it, for example from major structural changes like a loft conversion.

Foundations in old homes

More from Period Living

Period Living is the UK's best-selling period homes magazine. Get inspiration, ideas and advice straight to your door every month with a subscription.

Period houses were built with very shallow foundations by today’s standards but were able to accommodate a certain amount of movement, thanks to the use of flexible lime-based materials.

Unlike modern concrete strip foundations, pre-20th-century walls were built with brick ‘footings’, widening out at the base in a stepped pattern to spread the load.

Foundations should be deep enough to avoid movement in the ground caused by frost and seasonal moisture changes, so the stability of old footings (less than half a metre deep) can depend to a large extent on the type of ground they’re built on.

Chalk and rock are the firmest types of subsoil. But clay, as many gardeners can attest, has a nasty habit of drying out, shrinking and cracking in hot dry summers until it later recovers, swelling back into shape in wetter weather.

How do trees cause subsidence?

Historically, subsidence claims have tended to peak in years when there were long periods of drought, increasing the risk of ground shrinkage, which is exacerbated by trees.

Some of the worst offending trees are broadleaf species, such as:

- Poplars

- Oaks

- Willows

- Ash

- Plane and sycamore trees

- Fast-growing leylandii and eucalyptus.

Trees can also be an indirect cause of subsidence where moisture-seeking roots invade underground drains causing them to leak. Vegetation-related subsidence corresponds to the growing season from April to October, the damage usually reaching maximum severity in the autumn – when most insurance claims are submitted.

Large trees close to houses take moisture from the ground and can cause shrinkage and instability in foundations

- Check you have the right home contents and buildings insurance with our handy guide

Dealing with trees

The problem with cutting down large, thirsty trees is that the ground may then swell with the moisture that’s no longer being absorbed by the tree, with the risk that it can then push the foundations upwards. Known as ‘heave’, this is the opposite of subsidence, but equally destructive.

You also need to bear in mind that cutting down trees protected by Tree Preservation Orders or in Conservation Areas without consent can lead to prosecution.

- ‘Tree management’ is often a better approach. This aims to reduce the amount of moisture uptake, for example by ‘pollarding’ – severe pruning. However, some species like willows and cherries respond to pruning with vigorous new growth.

- ‘Root barriers’ are an alternative method of tree management, which involves excavating a deep, narrow trench between the tree and the building into which special large rigid plastic sheets are inserted. This offers the advantage of retaining attractive trees, while protecting the foundations.

Can I claim for subsidence on my insurance?

Most insurance claims for alleged subsidence are rejected because the cause lies elsewhere, such as poorly built conservatories pulling away from the house.

Of the valid claims, most are linked to trees and large shrubs close to the house extracting moisture from shrinkable clay subsoils.

How to deal with subsidence

What is underpinning?

The textbook response to subsidence is to excavate down to stable ground and pump tonnes of concrete into the void. But this is expensive and disruptive, and can actually create problems when applied to old buildings, setting up new stresses between the rigid repaired area and the remaining old walls.

Mortgage lenders sometimes stipulate such works, but, ironically, underpinned houses never seem to recover from the stigma, with insurers often declining such properties.

A more sensitive and less expensive approach with old buildings can be to lay a few courses of brick under the defective section of wall to re-establish contact with firm ground.

Other structural issues

Subsidence is not the only cause of cracks in property walls. Here are some other issues and how to solve them.

For even more advice, check out our guide to cracks and structural problems.

Bowing and leaning walls

The end walls of terraces can often be prone to bowing out or leaning. Unlike the main front and rear walls, which are typically connected by floor and ceiling joists, there may be very little holding side walls in place.

This is why cast-iron spreader plates and tie bars were commonly inserted to restrain the walls – like a metal corset. Also vulnerable are parapet walls at roof level and heavy gables over bay windows.

Where a wall is leaning outwards at its upper level, a common cause is ‘roof spread’. This is where the roof rafters have pushed the top of a wall out, because they are no longer being held in place by the ceiling joists. One clue to this can be seen in upstairs bedrooms where gaps to window frames are wider at the top than at the bottom.

Where walls have bowed out, you may see cracking to the interior plasterwork at the junction with internal walls and ceilings, along with gaps between the skirtings and the floor. One potential problem with walls that have travelled outwards is that the floor joists that used to rest in the wall may consequently have come loose. In this case, steel joist extenders can be fitted to lengthen the joists so they can reconnect with the wall.

Bowing walls can also be resecured by inserting discreet stainless steel wall ties to anchor them to the floor joists; these are a modern alternative to traditional ‘X’- or ‘S’-shaped tie bars.

Spreader plates and ‘S’ and ‘X’-shaped tie bars are inserted through the wall into floor joists to restrain a wall from bowing

Dealing with cracks

Most cracks in old buildings are of little significance. Often the building is just ‘getting comfortable’ as its shallow foundations adjust to ground changes during the year.

Cracking is more likely to occur where hard, modern plasters, cement renders and mortars have been applied to flexible old walls, but superficial cracks up to about 1mm wide are unlikely to be of any great concern.

Cracking is more likely to be serious where a crack extends right through the wall from the ground up and where vertical tapered cracking appears wider at the top.

Diagnosing the causes of cracking for insurance claims normally requires professional monitoring. It can take over 12 months to check whether cracks are ‘progressive’ or simply opening and closing with the seasons. But as long as the cracking has stabilised, and gets no worse year-on-year, in most cases no further action will be needed.

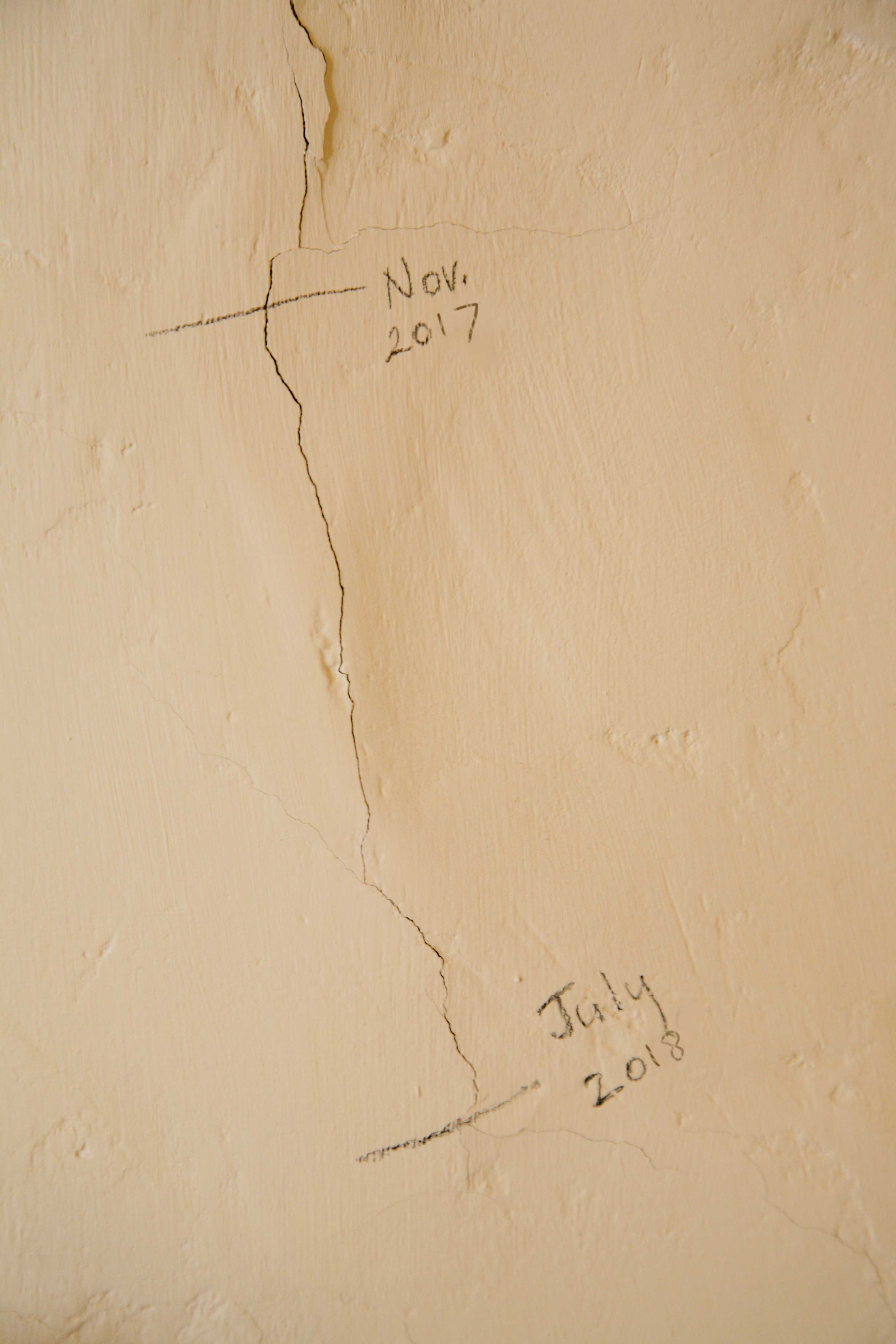

The simplest way to see if a crack is ‘live’ is to mark where it ends with a pencil and record the date. If the crack continues to grow, do the same again at regular intervals – rather like a height chart for growing children.

Marking a wall crack with pencil will help you to monitor whether it worsens over time

As well as shallow foundations, another common cause of cracking is structural alterations. Where internal walls have been removed, or windows replaced, it can set up new stresses, so the masonry needs to settle into a new position.

More concerning is when neighbours carry out illegal basement conversions, thereby undermining party walls and causing dangerous structural cracking in adjoining houses. If you or your neighbours are to do works to adjoining walls, make sure a party wall agreement is drawn up to mitigate any issues.

Be mindful when adding a modern extension that the new and old parts will move and settle at different rates

Differential movement: cracks between old and new parts of the building

Where you have different foundation depths adjoining each other, such as an old house with a modern extension, cracking can occur at the junction between the two structures due to different rates of movement.

One way to accommodate this is to provide a flexible joint between the two parts, allowing them to move harmlessly against each other without cracking. But differential movement is nothing new – similar problems can periodically arise where Victorian bay windows were built with shallower foundations than those to the main house.

More on renovation:

- How to renovate a house: an expert guide

- 16 costly renovation mistakes to avoid

- Exterior repairs: give your home a health check with these top tips

The Victorian House Manual | RRP £17.50 on Amazon

Want to take better care of your period home? This Haynes Manual by Ian Rock is the essential read for any owner of a Victorian (or Edwardian home).

Join our newsletter

Get small space home decor ideas, celeb inspiration, DIY tips and more, straight to your inbox!

Ian Rock MRICS is the chartered surveyor author of eight Haynes Property Manuals, and is the director of the RICS home survey price comparison website Rightsurvey.co.uk

-

This colourful home makeover has space for kitchen discos

This colourful home makeover has space for kitchen discosWhile the front of Leila and Joe's home features dark and moody chill-out spaces, the rest is light and bright and made for socialising

By Karen Wilson Published

-

How to paint a door and refresh your home instantly

How to paint a door and refresh your home instantlyPainting doors is easy with our expert advice. This is how to get professional results on front and internal doors.

By Claire Douglas Published

-

DIY transforms 1930s house into dream home

DIY transforms 1930s house into dream homeWith several renovations behind them, Mary and Paul had creative expertise to draw on when it came to transforming their 1930s house

By Alison Jones Published

-

12 easy ways to add curb appeal on a budget with DIY

12 easy ways to add curb appeal on a budget with DIYYou can give your home curb appeal at low cost. These are the DIY ways to boost its style

By Lucy Searle Published

-

5 invaluable design learnings from a festive Edwardian house renovation

5 invaluable design learnings from a festive Edwardian house renovationIf you're renovating a period property, here are 5 design tips we've picked up from this festive Edwardian renovation

By Ellen Finch Published

-

Real home: Glazed side extension creates the perfect garden link

Real home: Glazed side extension creates the perfect garden linkLouise Potter and husband Sean's extension has transformed their Victorian house, now a showcase for their collection of art, vintage finds and Scandinavian pieces

By Laurie Davidson Published

-

I tried this genius wallpaper hack, and it was perfect for my commitment issues

I tried this genius wallpaper hack, and it was perfect for my commitment issuesBeware: once you try this wallpaper hack, you'll never look back.

By Brittany Romano Published

-

Drew Barrymore's new FLOWER Home paint collection wants to give your walls a makeover

Drew Barrymore's new FLOWER Home paint collection wants to give your walls a makeoverDrew Barrymore FLOWER drops 27 brand-new paint shades, and every can is made from 100% post-consumer recycled plastic.

By Brittany Romano Published