It is almost impossible to pick out the most stunning treasures cared for by the National Trust.

In 2020, 125 years after it was founded, the National Trust’s portfolio of heritage properties alone numbers more than 500, ranging from historic houses and gardens, industrial monuments, to social history sites, most open to public view.

So make 2020 the year that you visit some National Trust properties.

Perhaps you might go for the Edwardian perfection of Polesden Lacey in Surrey, with Persian carpets and palazzo gold-carved panelling – so peaceful that the future King George VI and his Queen Elizabeth chose to honeymoon there.

The saloon of Polsedon Lacey, with its palazzo gold-carved panelling, where the future King George VI and his Queen Elizabeth chose to honeymoon - now in the care of the National Trust

Or it might be the delicate Chinese silk wallpaper in the Georgian manor of Saltram, Devon, its willowy figures almost as vivid 300 years after being handpainted onto mulberry paper.

Then there are riches by association, such as Shaw’s Corner, Hertfordshire, home to George Bernard Shaw for 44 years. Built in 1902, it exemplifies Arts and Crafts style; but the attraction lies also in the glamorous personalities who passed through the plain front door: Edward Elgar, Vivien Leigh and TE Lawrence among them.

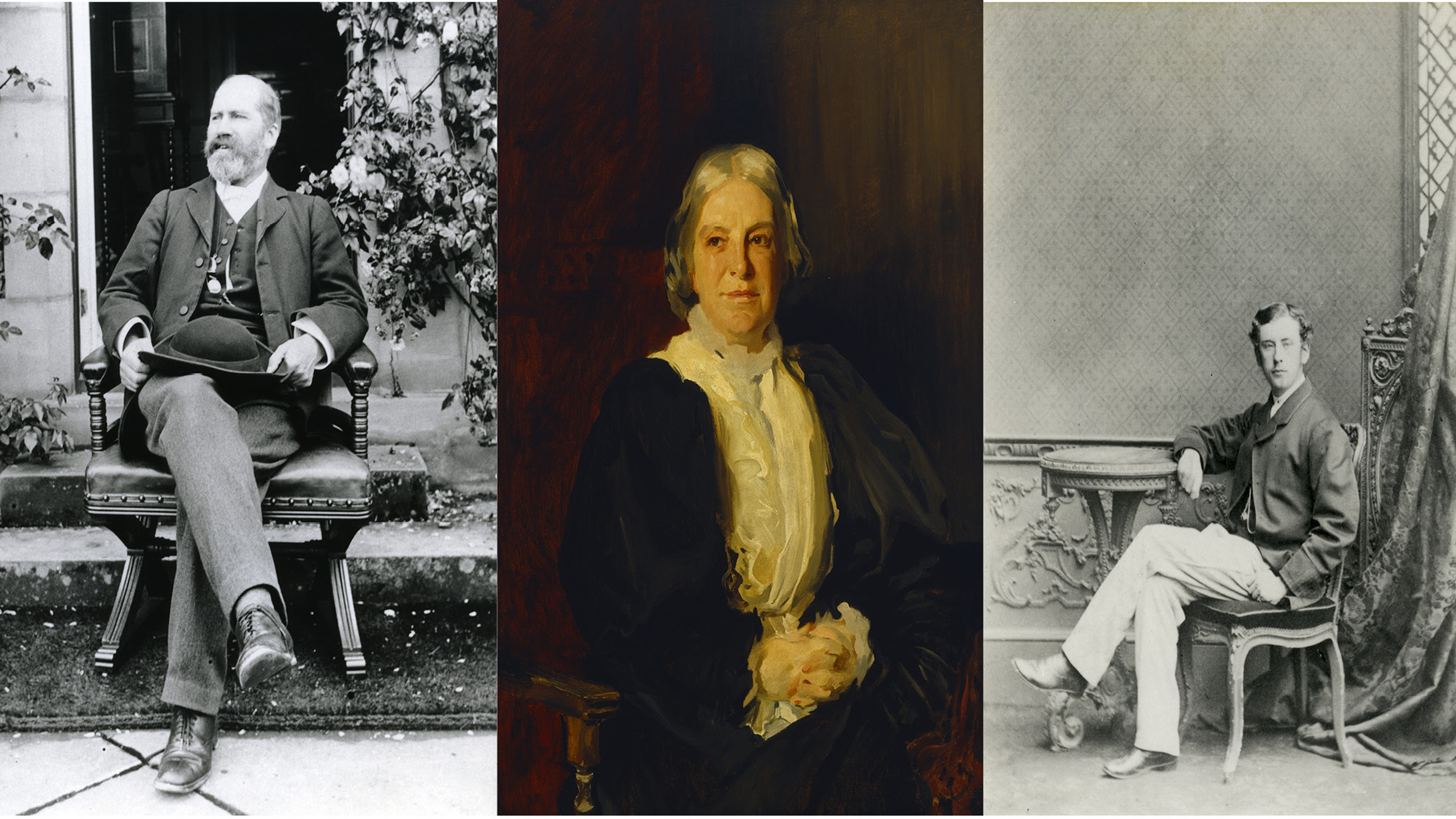

The three founders of the National Trust (from L-R): Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley; Octavia Hill, captured in John Singer Sargent's 1898 portrait; and solicitor Robert Hunter as a young man

The founders of the National Trust

What is indisputable is that all of the National Trust properties owe their survival to a determined trio: social reformer Octavia Hill, solicitor Robert Hunter, and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, who convened the first meeting of a new society in Great College Street, London, in February 1895.

Join our newsletter

Get small space home decor ideas, celeb inspiration, DIY tips and more, straight to your inbox!

In the 19th century there was already growing alarm that England’s natural and built heritage was under threat. London was gobbling up villages such as Camberwell and Finchley, cutting through wildflower meadows with soot-belching railways, and ancient manors were being sold to speculative developers.

Octavia was horrified. John Singer Sargent’s 1898 portrait shows a matronly woman, in self-effacing plain dress, glancing almost demurely to her side. Don’t be fooled: she was a moral force to be reckoned with.

No stranger to hardship – her bankrupt father had abandoned his family of eight – Octavia Hill firmly believed that the city-dwelling poor needed access to country air for their physical and moral well-being.

What better way to deliver than via a charitable institution dedicated to protecting and preserving places of historic interest and natural beauty for the benefit of the nation?

Alfriston Clergy, a rare 14th century Wealden Hall House in East Sussex, was the first property purchased by the National Trust in 1896 - at which time it was in a ruinous state, as pictured here in 1894

Restoration story: the National Trust's action plan

In 1896, the National Trust purchased its first building: Alfriston Clergy House, a 15th-century Sussex hall-house falling into wrack and ruin – so much so that the bishop had ordered its demolition. As Octavia noted, it was ‘tiny but beautiful’, complete with ancient orchard and views across the River Cuckmere.

It cost a nominal £10 (about £1,260 today), but that was the least of the Trust’s expenses. With help and advice from the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, founded some 20 years previously by William Morris, they agreed they would restore it ‘in so far as that odious word means preservation from decay’.

Alfriston Clergy house as it is today having been restored and conserved by the National Trust

The interior of the 14th century cottage at Alfriston Clergy House, East Sussex

Here was the start of a steep learning curve: how to fund repairs and maintenance? How to carry out difficult renovations sympathetically? And – perhaps most challenging of all - how to keep these buildings alive once saved?

Many great houses were acquired in lieu of death duties, thanks to a 1937 Act of Parliament – and it was the job of the wickedly sharp, and extremely knowledgeable, architectural historian James Lees-Milne to woo potential donors.

Max Hastings dubbed him ‘the man who saved England’. His renowned diaries are full of irresistible vignettes, gathered as he bicycled his way around stately homes: the Hoares, at Palladian Stourhead - with its world-class garden - describing how they were forced to eat rats during the Paris Commune; or Lord Berwick of Attingham complaining that ghosts had invaded his vacuum cleaner.

Stourhead was among the many stately home that James Lee-Milne persuaded the owners to gift to the National Trust

Magnificent to modest: properties in the National Trust's care

Other donors brought into the fold humbler aspects of English life. Beatrix Potter, a close friend of Canon Rawnsley, left to the Trust 15 farms and 4,000 acres of her beloved Lake District - along with strict instructions that the oak furniture, cared for by generations of farmers’ wives, had to be retained.

Ursula Blackwell bequeathed 2 Willow Road, Hampstead, in 1991: a concrete and redbrick house designed by her late husband, architect Ernö Goldfinger, whose fury knew no bounds when neighbour Ian Fleming – who thoroughly disliked the house – named a Bond villain after him.

Beatrix Potter bequeathed her beloved Hill Top, her Lake District home, and much more to the National Trust

More modest properties include two of The Beatles’ childhood homes in Liverpool, and 575 Wandsworth Road, a 19th-century terrace beautified with handcarved fretwork by its owner, Kenyan polymath Khadambi Asalache.

The Trust’s collections, too, are vastly varied. How to compare the magnificent art of Petworth House in West Sussex – including such masterpieces as Blake’s The Last Judgement – with the quirky 22,000 objects amassed by Charles Paget Wade at his Cotswold home of Snowshill: everything from 19th-century Samurai armour to toy trains.

Some of the intriguing collection on display at Snowshill Manor in the Cotswolds

Science meets conservation

Fast on the heels of this growing list of Trust acquisitions, of course, came the responsibility for preserving and conserving them. Sir Winston Churchill’s home of Chartwell, in Kent, was one of the first to introduce time-restricted tickets: by 1969, it was attracting 163,500 tourists a year. Blinds began to be routinely put up to protect artworks, fabrics and furniture. As technology advanced, humidity and temperature were able to be more accurately monitored and controlled.

‘In the 1930s and immediate post-war period, our approach would have very much followed traditional ways servants looked after the buildings. From the 1970s onwards, conservation evolved into a more scientific discipline,’ explains Dr Nigel Blades, conservation adviser at the Trust.

Humidity and temperature are carefully monitored and controlled in many of the National Trust properties, such as Petworth House, to preserve the collections and works of art

After the Second World War, conservators enthusiastically embraced industrial products newly on the market. ‘But we’ve become more aware of the risk of those sorts of materials. Today’s principles are about reversibility of treatment: you don’t use an adhesive you won’t be able to dissolve with a solvent in the future.’ Detailed records are kept, and repairs – where possible – are often deliberately left visible so they can be distinguished from the original.

Other recent advances include scientific analysis of colours, so as exact a dye-match as possible can be recreated for a repair, using modern materials less light-sensitive than the originals. One of the Trust’s specialist conservation studios – housed in a converted barn at Knole, near Sevenoaks – is open to visitors, who regularly ask advice about preserving their own family heirlooms.

Climate-change, extreme weather events, more voracious pests – such as a particularly resilient silverfish newly arrived from the continent – are all issues increasingly facing conservators.

There have been a number of innovative exhibitions and ways of presenting the property to visitors at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire

Keeping history alive at the National Trust

Innovation isn’t limited to conservation, of course; it’s evident in the Trust’s presentation of houses, too. Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, to take but one example, has seen everything from cutting-edge virtual reality – where artist Mat Collishaw restaged William Fox Talbot’s first photography exhibition of 1839 - to the recent ‘Feel at home’ initiative, with visitors invited to bring their slippers, sit in an easy chair, and do some knitting.

A celebration of the contemporary is also evident in Trust New Art, showcasing up-to-the-minute installations and multi-media.

‘We want to hold on to the best of the past – preserving it beautifully - but also ensure our places are relevant and dynamic,’ says John Orna- Ornstein, director of culture and engagement.

Hilary McGrady, director-general of the National Trust

National Trust investing in the future

As to future-proofing the charity, Hilary McGrady, director-general since March 2018, believes investment is the key. The Trust has 5.6 million members and spends more than £2.5 million a week on conservation projects.

‘If the Trust is going to be relevant in people’s lives 125 years from now, we need to be prepared to meet them halfway. We have to think about not just the places in our care, but the places that matter to people beyond our ownership. It means a greater emphasis on partnership-working, and thinking creatively about experiences that inspire and delight a whole range of people,’ says Hilary.

‘We provide access to amazing places, enabling people to experience them in ways that deepen their understanding. Heritage is such a powerful force for good because it can bind people together, especially at a time when the nation is so divided.’

Octavia Hill was a forward-thinker, too. Towards the end of her life, she fervently told friends they must never blindly follow in her footsteps: ‘It is the spirit not the dead form that should be perpetuated.'

-

Regency garden ideas — 7 ways to create an elegant, Bridgerton-style outdoor space

Regency garden ideas — 7 ways to create an elegant, Bridgerton-style outdoor spaceLooking for regency garden ideas? We've asked the pros for their top design and gardening tricks that will add elegance and refinement to your backyard

By Eve Smallman Published

-

Could your fireworks display be breaking the law? Here's what you need to know

Could your fireworks display be breaking the law? Here's what you need to knowLooking forward to a Bonfire Night display, or planning fireworks as a birthday surprise? These are the fireworks laws you need to know about

By Anna Cottrell Published

-

Garden centre preferred to shopping online – discover the best garden centres in the UK

Garden centre preferred to shopping online – discover the best garden centres in the UKVisit your nearest garden centre or nursery this weekend to discover a wealth of plant inspiration, homeware, good food and more. We've rounded up the very best

By Melanie Griffiths Published

-

Quit the gym: gardening is better for you – and here's why

Quit the gym: gardening is better for you – and here's whyNew survey suggests people feel better when they garden than when exercising, cleaning, or achieving at work

By Anna Cottrell Published

-

Best garden plants for health

Best garden plants for healthThe best garden plants for health will help you sleep better, alleviate stress, and even help cure a common cold. Here's our pick of the most potent plants and herbs you can grow yourself

By Anna Cottrell Last updated

-

Cleaning and gardening better than workout says new survey

Cleaning and gardening better than workout says new surveyTackling cleaning and gardening has more benefits than going to the gym: you'll save money, boost your mental health and get a free workout

By Amelia Smith Published